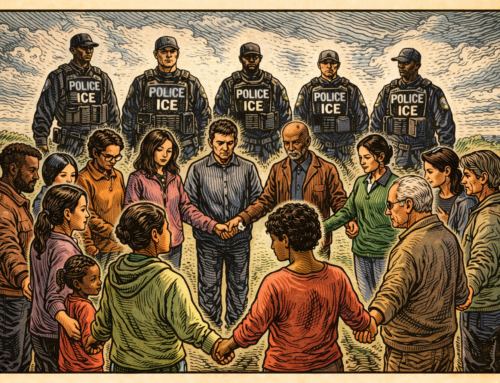

One of my students, Polina Shneyderman, recently posted her results using Zhīzǐ Chǐ Tāng as follows:

One of my students, Polina Shneyderman, recently posted her results using Zhīzǐ Chǐ Tāng as follows:

I wanted to share a case that was helped so much by a tiny formula I learned from Sharon in her GMP. I have a patient who is a textbook Guìzhī Tāng pattern and who has done really well on different modifications of Guìzhī Tāng. She has Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, where her body produces too much collagen, and as a result, she has heart palpitations, agitation, and very loose joints. Guìzhī Tāng has helped with heart palpitations, periods, cold, and body aches. One thing I could not tackle was her waking up before her alarm in the morning, feeling a sense of terror or fear of missing something important.

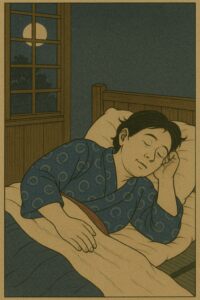

I learned from Sharon that there is a formula called Zhīzǐ Chǐ Tāng—zhīzǐ and dàndòuchǐ—and that it can help with this kind of terror. I added these two herbs to her formula, and she now sleeps soundly and peacefully until her alarm wakes her up. The bonus—her blood pressure is normal now, too—patients with EDS tend to have dangerously low blood pressure.

Just wanted to share a success story and thank Sharon and other White Pine mentors who help us all be better clinicians.

In the next post, I will discuss this Zhīzǐ Chǐ Tāng formula pattern.

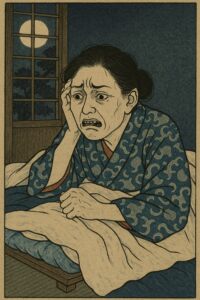

Insomnia is as common as its roots are complex. When I learn that a patient has difficulty sleeping, the image that comes to mind is of the

sun sinking in the west toward the deep north, living below the horizon until dawn breaks. I see my patient’s nighttime cycle overlaid on this, noticing how their yáng — their consciousness, their life force — fails to follow the sun’s hibernation in the north. Does their yáng have difficulty following the sun in the west, or does it follow the sun but have difficulty staying stored in the north? Does it rise before the sun rises in the east? In the clinic, I may ask my patient whether they have difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep, or waking too early. Still, in my mind’s eye, I am seeing their relationship to heavenly movements as the Huángdì neijing instructs us to do.

By itself, without any further differentiation, the symptom of insomnia simply means that yáng is not rooting at night with the sun. In my clinic and in the teachings on diagnosis of the Graduate Mentorship Program, I always temporarily set aside the symptom of insomnia so I can clearly see the pattern that explains the insomnia. Once I can see the pattern, the insomnia makes sense. Without this, we may tend to look for “insomnia formulas,” which will yield inferior results.

In this series of posts, I will discuss several pathological mechanisms that contribute to difficulty sleeping and how to differentiate them. To do this, an understanding of physiology is invaluable.

For example, when we understand that our bodies follow the rhythms of heaven as laid out in the Huángdì neijing, we know that our bodies follow the descent of the sun, which is yáng, in the west. In our bodies, descent depends primarily on three of the six conformations:

- Yángmíng

Being the conformation of the dry metal of the west, yángmíng is the primary great sweeping motion from the south to the north. It corresponds loosely to the downward progression of our digestive tract. - Shàoyáng

Shàoyáng is the pivoting conformation and the great sweeping motion that pivots our yáng from yángmíng’s downward motion to become the rooted ministerial fire. - Shaoyīn

While yángmíng and shàoyáng are yáng conformations and hence depend on being open and free, shaoyīn is a yīn conformation that relies on being strong enough to draw in and store the yáng that follows the sun.

Hence, insomnia, characterized by difficulty falling asleep, most often involves at least one of these conformations. This is in contrast to difficulty staying asleep or waking too early, which most often involves different conformations.

- Yángmíng

In which one of the stations along the yángmíng track (chest, diaphragm, epigastrium, large intestine) is not open enough to allow the patient’s yáng to settle in the west. - Shàoyáng

In which shàoyáng is not free-moving enough to pivot and allow the descending yáng to root. - Shaoyīn

In which shaoyīn is too weak to draw in and store the descending yang.

A common example of difficulty falling asleep because the west is not fully open in my patient from my practice is the Bànxià Xiè Xīn Tāng pattern. In this mixed hot-and-cold, excess-and-deficiency pattern, the patient’s epigastric area is not fully open. Hence, yáng has difficulty descending through this central, spleen/stomach axis. When I see the Bànxià Xiè Xīn Tāng pattern, it is frequently accompanied by difficulty falling asleep. Rather than using this formula to treat insomnia, I explain the insomnia with the presenting pattern. Of course, a Dà Cháihú Tāng or Táohé Chéng Qì Tāng pattern could also explain insomnia with difficulty falling asleep. Many patterns can explain trouble sleeping.

In this series of posts, we will examine several interesting formula patterns that can explain insomnia. We will be looking at the formula pattern as an image that matches the precise way the patient’s body cannot match heaven’s movements.

When we learn to see through the lens of these patterns, our diagnosis and treatment can be very precise.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.