As a continuation of the discussion on using classical formulas for sleep issues, I will now introduce two very effective zhīzǐformulas: Zhīzǐ Chǐ Tāng and Zhīzǐ Gānjiāng Tāng. As you recall in the previous post, my student Sylvia described the use of Zhīzǐ Chǐ Tāng and how she differentiated the pattern.

First, let’s talk about zhīzǐ. It is the fruit of the gardenia plant. In his poem, Shěn Zhòu[1] of the Ming Dynasty described the gardenia flower like this:

“雪魂冰花凉气清”

“雪魂冰花凉气清”

Snow ghost, ice flower, with its clear, cold Qi

According to Shen Nong Ben Cao Jing, zhīzǐ‘s flavor is bitter and its nature is cold. It is said to enter the heart, lung, stomach, liver, and San Jiao channels.[2] It is effective in discharging fire and dispelling vexation, clearing heat through benefiting urination, cooling blood, and resolving toxins.

Zhīzǐ‘s key action is to disinhibit the shàoyáng great sweeping motion. The motion of shàoyáng is to pivot. The shàoyáng pivot is responsible for pivoting imperial fire, which has descended into the body through the joint motions of shàoyīn and yángmíng, into its position within the body as ministerial fire. If the shàoyáng pivot motion is inhibited, the descending heat, which is none other than the physiological life-force, accumulates and becomes pathological. This pathological heat easily affects all three jiāo. Zhīzǐ disinhibits the pivot so that the warm and life-giving flow of the life force can flow as the ministerial fire and not as pathological heat. As Dr. Qīsays, “Looking at the records of traditional Chinese medicine throughout the dynasties, zhīzǐ is the only one among the numerous heat-clearing herbs that has the effect of clearing the three jiāos.”[3] This helps explain that zhīzǐ is a shàoyáng herb, as bitter cold yángmíng herbs generally address a single jiāo.

Zhīzǐ‘s particular strength is in disinhibiting the pivot for heat that is agitating the spirit or the blood and causing the urine to be concentrated yellow or hot. Hence, when there is a pattern of inhibited pivot with an agitated spirit and yellow urine, zhīzǐ is very effective.

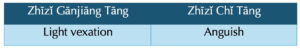

There are two formulas I use for “agitated spirit” when this manifests particularly as insomnia. In the case of the two zhīzǐ formulas, the heart is agitated because heat is unable to descend and root. The inhibited pivot prevents the heat from rooting. However, the location of the area affected by the blocked pivot differs between the two formulas. I’ll differentiate them below:

Zhīzǐ Gānjiāng Tāng is a teeny tiny formula made up of 14 pieces of zhīzǐ and 2 liǎng of gānjiāng. Modern weight equivalences are generally zhīzǐ 9-12 g, and gānjiāng 6 g. The original text, line 80, says, If purging has been used and the person subsequently develops light vexation, Zhīzǐ Gānjiāng Tāng is indicated.”

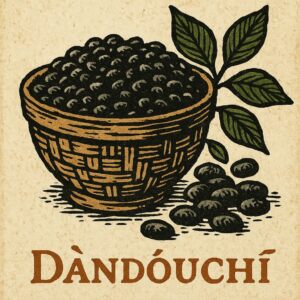

Zhīzǐ Chǐ Tāng is also a teeny tiny formula, made up of 14 pieces of zhīzǐ and 4 ge of dàndòuchǐ. Modern weight equivalences are generally zhīzǐ 9-12 and dàndòuchǐ 12-30 g. Line 76 of the Shānghán lùn says, “After sweating, vomiting, or purging, there is deficiency vexation and inability to sleep. If it is severe, with tossing and turning and anguish in the heart, Zhīzǐ Chǐ Tāng rules.”In a pattern of inhibited pivot motion with insomnia, I use Zhīzǐ Gānjiāng Tāng when the insomnia is characterized by too much thinking. The person will agree that when they wake up, they start thinking and can’t turn it off. Zhīzǐ Gānjiāng Tāng is particularly effective in these cases.

In a pattern of inhibited pivot motion with insomnia, I use Zhīzǐ Chǐ Tāng when the patient wakes up with a distinct feeling of anguish.

Most of the time, when I ask the patient about these characteristics of their insomnia, they are quite clear about them. Many times, when I ask, using the word “anguish,” patients have sat up straight and exclaimed, “Yes!” as if I’d hit the nail on the head. Many times I ask, and the patient cannot relate to either overthinking or anguish. They may say they simply wake up and can’t go back to sleep, even though they are not agitated by thoughts or anguish. In these cases, a zhīzǐ formula is not appropriate.

Most of the time, when I ask the patient about these characteristics of their insomnia, they are quite clear about them. Many times, when I ask, using the word “anguish,” patients have sat up straight and exclaimed, “Yes!” as if I’d hit the nail on the head. Many times I ask, and the patient cannot relate to either overthinking or anguish. They may say they simply wake up and can’t go back to sleep, even though they are not agitated by thoughts or anguish. In these cases, a zhīzǐ formula is not appropriate.

Why is dàndòuchǐ used? We will look at this in the next post! It is a fascinating and often misunderstood herb. We will also consider why gānjiāng is used. Stay tuned.

[1] Shěn Zhòu (沈周, 1427–1509) was one of the greatest painters, calligraphers, and poets of the Ming Dynasty. He is considered a foundational figure of the Wu School (吴门画派) of painting in Suzhou and a major cultural influence in late imperial China.

[2] Formulas and Strategies

[3] 柒大夫, Dr. Qi, published on https://www.jingfangpai.cn/p/10053716/

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.